Midsommar's masterful meditation on grief

Midsommar is less of a horror movie and more of a haunting fairytale about a grieving woman finding family in the last place she expected — also, Florence Pugh rules.

(Midsommar spoilers to follow)

It comes in at the 8:41 mark, a scream so guttural that words aren’t needed to convey the magnitude of the pain Dani is releasing into the speaker of her phone. Christian, on the other end of the call that Dani is howling into, knows what just happened without his girlfriend uttering a word other than “no” — she repeats this word between screams. The howl and “no”s morph into a singular sound of sadness. Her bipolar sister, Terri, has just killed her mom, dad, and herself by filling their home with carbon monoxide immediately after sending Dani an email that read, “i cant anymore - everything’s black - mom and dad are coming too. goodbye.”, after which Christian told a concerned Dani that Terri only sent that email as an “obvious ploy for attention.” It turns out, despite Christian’s advice to ignore her, Terri wasn’t merely seeking attention, she really did kill every remaining member of Dani’s immediate family, and Dani is suddenly alone in the world for the first time in her life with nothing more than a reluctant boyfriend to comfort her. And with that unfathomable tragedy, Ari Aster’s Midsommar begins.

Released last July to critical acclaim, Midsommar is a horror movie about a group of graduate students — Dani (Florence Pugh), Christian (Jack Reynor), and his friends — who take a trip to Sweden to mostly observe and eventually participate in a midsummer celebration at a commune called the Harga in the middle of absolutely nowhere. The commune is located on a sprawling grass field between a vast forest. It stays light nearly every hour of the day. The forest sheltering the commune from the outside world feels alive. The trees move and the flowers pulsate like beating hearts. There’s something seriously off with the Harga. Two elders commit suicide by jumping off a cliff while the rest of the commune looks on in admiration in a ceremony known as attestupa. There’s a lone caged bear and a mysterious tent that nobody is allowed into. Something sinister is brewing beneath the surface and seeping through the cracks — what exactly is unknown for so much of the film until it eventually erupts into flames. Psychedelics are consumed on multiple occasions — sometimes willingly, other times reluctantly. The entire movie is a trip, from the story itself to the unsettling score composed by Bobby Krlic to the way it’s filmed. It reminded me in many ways of Annihilation, another movie that tackles subjects like grief, depression, and healing through a trippy journey to a place that doesn’t feel at all akin to our world even though it takes place right next door. By the time Natalie Portman’s character reappears out of The Shimmer in Annihilation, she’s undergone a transformation. Likewise, Dani’s experience in Sweden changes the very fabric of her existence. By the end, she’s not really Dani anymore — at least not the version presented to us two hours earlier and sustained for almost all of its runtime.

The use of psychedelics feels like an emblem to anxiety, much like The Shimmer in Annihlation served as a metaphor for depression. Throughout the film, Dani suffers from anxiety attacks whenever something or someone triggers a memory of her family’s death — it happens once while she’s tripping. When she wakes up in the middle of a field, she has no idea how long she slept. She loses track of time. Likewise, in Annihilation, Portman’s character wakes up without remembering falling asleep; she’s shocked to learn how long she’s actually been inside The Shimmer. It feels like she’s only just gotten there.

As Vulture’s Angelica Jade Bastién wrote at the time:

This decision by (Annihilation director Alex Garland) can first read as an easy narrative device to bypass fleshing out the particulars of the early part of their trip. But their loss of time read to me as a familiar experience of a depressive episode, where time moves in unnatural ways. Where you wake up sometime in the afternoon, the days an uneasy blur, but very aware of the taste of regret on your tongue.

[…]

The plants they encounter are strangely drained of color, as is the unnerving shark-alligator hybrid. Concrete walls are covered in vegetation that reads as cancerous growth, tumors awash in psychedelic color. From certain angles, trees scan as humanoid in shape. Depression is like this. It consumes everything in its path, warping it madly. The world is drained of vibrancy or easy understanding. The finest meal can taste like ash. Your body is no longer your own, but a weapon formed against you.

Everything in Sweden feels upside down to Dani. That’s not just Aster disorienting the audience for the sake of disorientation. That’s not just the drugs talking. It’s meant to mirror Dani’s perception. Since the tragedy, her entire world is warped. She’s floating off in space like an untethered cosmonaut. She’s searching for structure. For support. For things to appear right-side up again.

I don’t normally like horror movies. As is also the case with superhero movies, there are notable exceptions. But I don’t think I’ve ever loved a horror movie. Midsommar is an exception. It came out in July, but I didn’t watch it until this past week because, well, I figured it wasn’t my kind of movie. Boy, am I an idiot. I loved it. I mostly approve of the nominations and winners at the 92nd Academy Awards, although I have a few nitpicks, but after watching Midsommar, I think it’s a goddamn travesty that a movie like Joker got a Best Picture nom over a masterpiece like Midsommar. Midsommar (available for streaming on Prime, by the way) is very much my kind of movie. It’s my kind of movie because as much as it might be a horror flick, it aspires to be so much more than that and successfully breaks free from the restraints of the genre. It’s more of a breakup movie that offers a careful meditation on grief and healing than a horror movie. It’s disturbing, jarring, fucked up beyond belief, and at times, a grueling watch, but the reward that only manifests itself in the final seconds of a 148-minute movie makes the process worth enduring. The midsummer celebration that Dani attends only happens every 90 years, but believe me when I say that it’s worth the wait.

The difference between Midsommar and ordinary horror movies, much like the difference between Birds of Prey and ordinary superhero movies, is that it’s more of a human story than a horror movie. The movie might be outlandish and improbable, but it’s grounded in humanity. While there’s no doubt Midsommar delivers terror, it cares more about Dani’s personal journey than scaring the audience. In Midsommar, the personal journey supersedes genre.

At its most basic level, it’s a story about a girl trying to heal. It just takes her down an extraordinarily unordinary path to healing.

The girl in question is Dani, a psychology grad student who loses her entire family in the opening nine minutes and for 147 of 148 minutes is stuck in a shitty relationship with a shitty man masquerading as a good guy. She’s played by Florence Pugh, who as Vulture’s David Edelstein wrote in his review of the film, “bends Midsommar toward her.” Make no mistake about it: She is the movie. It doesn’t work without her mesmerizing performance as an anxious, depressed, and lost woman searching for a path to recovery.

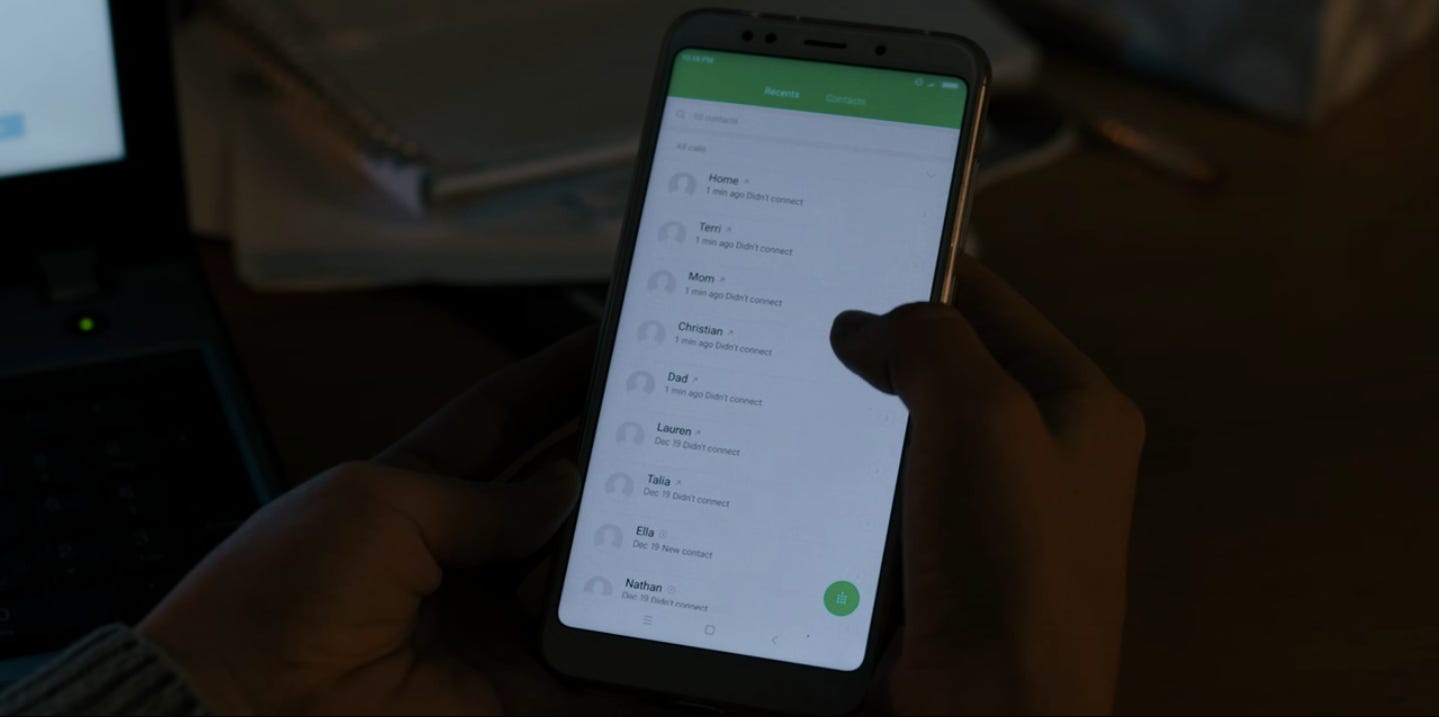

If Midsommar were a normal horror movie, its plot would entail Dani and the rest of the group trying to escape from the Swedish commune before they are killed or worse, become one of them. Instead, it goes down the opposite path. It’s about Dani finding a legitimate reason to stay instead of fleeing to her unfulfilling past life. It’s about Dani finding family — someone to grieve with her, to genuinely care about her well being, to give her a sense of belonging and purpose — and the strength to break up with Christian. She’s searching for connection, a journey that is mapped out in the opening minutes when the camera cuts to a close-up of her phone and eight of her nine most-recent calls read “Didn’t connect.”

Clearly, she won’t find that with Christian, which she knows, but refuses to accept until the final few moments. When Dani calls Christian twice in the opening nine minutes, he answers both times. The first time she calls about her sister’s worrying emails, he dismisses her, annoyed that she has the audacity to be concerned about her bipolar sister. After the aforementioned second call, he leaves his friends at the pizza joint to hold her while she writhes in anguish. But to call him a supportive partner would be like calling Clay Travis an intellectual. Moments before she called, Christian was debating with his friends if he should break up with her. The only reason he gives for not ending it isn’t that he’s afraid of hurting her, but that he’s worried he’ll regret his choice and won’t be able to win her back. Not only is he a dick, he’s also a coward.

His friends are no better. When Christian’s phone rings for a second time, Mark (Will Poulter) says Dani’s need for support is “literally abuse. She’s abusing you.” He wants Christian to dump Dani so that he can “impregnate” other girls — a word choice that can be best described as unfortunate foreshadowing, not that Mark will be alive to know it.

When she calls, he heads over to her place, but he’s not running to offer his support; he’s trudging through the snow as if he’s slowly stepping toward his grave. Suddenly, he’s trapped in a doomed relationship. He can’t possibly break up with her now that her parents and sister died, right? Even for a dick like him, that’s messed up.

If all of this makes Midsommar seem like a breakup movie, that’s because it is.

“I felt like Dani at the time of writing it, but I definitely have been on both sides of that dynamic,” Aster told The Washington Post. “I’ve been in relationships where I feel that I care a lot more than the partner, and I’m clinging to something and don’t want to let go of something even after it stops working. And then I’ve been in the place of wanting to leave and being either afraid to leave because I’m worrying about regretting it, or because I don’t want to hurt the other person. So you sort of just stay in that limbo.”

The snow is important. Aster makes a point to emphasize the seasons. It’s winter when the film begins — when Dani loses her family. As Dani sobs in Christian’s lap, the blizzard devours the frame of the window behind them. The camera slowly draws nearer to the blizzard until the falling snow is all that fills the frame. The opening credits flash on screen, but the words are difficult to read. The blizzard smothers them.

The time of day carries importance, as well. At home, we never see Dani and Christian during the day. It’s always dark outside. Both of these characteristics, the time of day and year, serve as foils to what comes later in Sweden — in the summer, in nearly unending daylight.

Before they get to that place, listening in on their conversations is like walking barefoot across a field of crunchy snow. Shortly after the tragedy, Dani learns from Christian’s friends that they — Christian included — are traveling to Sweden for a month-and-a-half. They leave in two weeks. Christian never told Dani. She confronts him. Deploying a combination of aloofness and passive aggressive petulance, he manages to flip it around on her so that she ends up apologizing to him. It’s gaslighting at its absolute peak.

Christian: “I told you I wanted to go to Sweden.”

Dani: “No, you said it would be cool to go.”

Christian: “Yeah, and then I got the opportunity, and I decided to do it.”

Dani: “Look, I don’t mind you going, I just wish you would’ve told me. That’s all.”

Christian: “Well, I just apologized, Dani.”

Dani: “You didn’t apologize. You said ‘sorry,’ which sounds more like ‘too bad.’”

Christian: “Maybe I should just go home.”

Dani: “What? No! No! I’m just trying to understand.”

Christian: “And I’m trying to apologize.”

Dani: “And I don’t need an apology. I don’t. I just wanted to talk about it. That’s all.”

Christian: “I really think I should just leave.”

Dani: “No, no, no, no, no. Please, please. I’m not trying to attack you.”

Christian: “It really feels like you are.”

Dani: “Well, then I’m sorry. I just got confused. I’m sorry.”

The conversation begins with Dani in the doorway and Christian at a nearby desk, but the camera centers itself on Dani and places Christian in the mirror sitting next to her. Aster frequently uses mirrors throughout the film — not as a method to scare the audience in the classic horror-movie trope, but as a way to further hammer home the themes of isolation and distance. The mirrors, I think, serve as a method to show how Dani and Christian — later, Christian and his friends when he breaks the news that he invited Dani without asking their permission first; they’re stunned — are operating in completely different spaces, seeing the same thing in entirely different ways with a lens between them.

The argument takes place before the 18-minute mark of the film. It’s clear in those opening 18 minutes that Dani won’t ever find comfort in Christian unless he undergoes a remarkable transformation. There’s a level of disconnect in their relationship that can’t be fixed unless they try to repair it, but Christian has no desire to do so even though Dani is clinging onto him as her last connection in a world that has fucked her over.

“In this film, Dani is the protagonist and Christian is, for all intents and purposes, a foil,” Aster said. “I wanted him to be somebody that people could relate to … but in the context of this film, he is the antagonist and, ultimately, an obstacle to Dani as far as, you know, achieving what she needs and finding any sort of peace.”

She also won’t find comfort in his friends. When Christian reveals to his friends that he gave Dani a pity invite to Sweden mere moments before she comes up to their apartment, none of them openly resist. None of them are overtly rude or mean to her. On the surface, they’re amiable. But there’s an underlying tension. She walks through the door. Mark gets up and asks Christian to help him with something; they disappear down the hall. Josh (William Jackson Harper) stands up, walks away to microwave whatever is in his mug, and doesn’t return, choosing to read in the kitchen while Pelle (Vilhelm Blomgren) makes small talk with Dani on the couch. Pelle, the friend who grew up in the Harga and has invited them to attend the midsummer festival back at his home in Sweden, is the only one who shows an interest in Dani. As we learn later, his motivations are sinister, but also genuine — the latter ends up mattering more than the former, even to Dani.

When he tells Dani that he was sorry to hear about her family, she feels the emotions bubbling toward the surface and makes a quick escape to the bathroom, where she can cry alone. The thing about Dani is that she always grieves alone. We already know Christian doesn’t really want to be there for her. He treats comforting her more like a summer job his parents forced him to get rather than something he actually wants. So, whenever she feels the tears welling, she bolts — to the bathroom in apartments and airplanes or the nearest isolated space. Anywhere she can be alone with her feelings. The empty space is her safe space.

She’s truly alone — just like her sister, who didn’t want to die alone, so she took her parents with her to wherever it is we go when our time here is up. i cant anymore - everything’s black - mom and dad are coming too. goodbye. Pugh’s portrayal of grief hits like a sledgehammer. She’s mesmerizing, playing a mix of vulnerable and a force of nature. She’s a blizzard of depression and anxiety. There’s the scream and also the spectrum of emotions that dances across her face like a torch on a pitch-black night, like an ember in the needles of a dried-out pine. As Edelstein wrote, “Her face is so wide and open that she seems to have nowhere to hide her emotions.”

Dani’s isolation only continues in Sweden. She’s disturbed when she witnesses the wretched suicide ceremony, but Christian fails to provide her with any measure of comfort. Instead, he rationalizes it.

“It’s cultural, you know? We stick our elders in nursing homes. I’m sure they find that disturbing. I think we really need to just at least try to acclimate,” he says. Imagine having the audacity to say that to someone who just lost her entire family to her sister’s suicide. This dude is the absolute worst.

At the village, the group meets an engaged English couple, Simon and Connie. They serve as a foil to Dani and Christian. When Connie asks how long they’ve been together, Christian incorrectly answers three-and-a-half years. Dani corrects him. It’s really been four years. The sequence is shot in such a way that illustrates the disconnect between Dani and Christian compared to the connection Simon and Connie share, with Dani and Christian standing awkwardly apart like a shy middle school couple reuniting after summer break, and Simon and Connie standing together the way normal couples do.

She’s not the only one who is alone. All of the foreigners who fall victim to the Harga die when they’re led away from the rest of the group. Mark, enticed by a woman, wanders off. We never see him alive again. Simon and Connie are maliciously split up by the Harga. Once apart, they disappear; later, we hear a woman’s scream in the distance. Josh is killed when he sneaks out in the middle of the night to trespass on holy ground for the sake of his thesis.

Isolation is everywhere in Midsommar. From the premise (traveling to a far away village), to Dani being present despite nobody in the group really wanting her there (with the notable exception of the Harga), to Dani grieving alone (while tripping shortly after arrival, she runs away from the group when she feels a panic attack coming), to the way mostly everyone dies. Dani is terrified of being alone. It’s why she stays with Christian when he so clearly has no desire to ever be what she needs him to be. It’s why she dreams that Christian and his friends sneak out in the middle of the night to flee the village without her. She’s terrified of being alone without recognizing that she’s already alone.

The twist is that Dani ends up finding belonging in Sweden, but not with Christian. The trip doesn’t bring them closer together, but only further apart. She finds her family in the most unlikely of places: the Harga itself.

It’s a surprise to her. But not to them. When they arrive, one of the elders greets the Americans. He tells Christian, Mark, and Josh, “Welcome.” He turns to Dani and says, “Welcome home.” In that sense, it’s not much of a surprise. Like all great movies, Midsommar sprinkles enough breadcrumbs along the way that when the ending hits, you’re able to step back and retrace the trail, but not too many breadcrumbs that the ending is spoiled before it arrives.

Aster deftly presents the Harga as terrifying, but not in a cartoonish way. You don’t agree with their belief that it’s better for the old to commit suicide than to continue on living their lives until they die of natural causes, but you believe that they’re sincere in their beliefs. They’re not killing their old with evil motives. They’re misguided, but at least mean well.

It’s a difficult line to straddle. But Midsommar straddles it.

"I tried to make this a place where you could be indoctrinated as you watched,” Aster told Vice. “A place where you could find yourself at home, because ultimately, that's what a group like this can be to others — a potential home to anyone seeking a home.”

Which is what she finds. Dani celebrates her birthday while in Sweden. Christian forgets, because if he can’t remember how long they’ve been together, how can he be expected to remember her birthday? Pelle doesn’t forget. He surprises her with a gift. Later, when she’s trying to reckon with the double suicide they all witnessed, he tells her that he lost his parents in a fire (hint, hint) and understands what she’s going through.

“Yet my difference is, I never got the chance to feel lost, because I had a family — here. Where everyone embraced me. And swept me up. And I was raised by a community that doesn’t bicker over what’s theirs and what’s not theirs. That’s what you were given. But I have always felt held. By a family. A real family. Which everyone deserves. And you deserve,” he says.

He takes her hand. Concerned what it could look like to Christian, who is absent (per usual), she tries to pull away. He presses on undeterred. Pelle, while remaining as equally perverted as the rest of the Harga, understands her grief and what she’s looking for that she’s yet to find and will never find in Christian, but will eventually come to find in the Harga.

“He’s what I’m talking about. He’s my good friend and I like him, but Dani, do you feel held by him? Does he feel like home to you?” Pelle asks.

On their final day, tripping on psychedelics again, she manages to accidentally win a dancing competition over every other young woman at the Harga, making her the May Queen. Christian, sitting amongst the audience, picks at the grass as his girlfriend dances her way to first place. He’s uninterested in Dani’s accomplishment, even though it’s the first time we’ve seen Dani entirely happy since the incident. She notices his apathy.

We’re used to seeing her face covered in a number of emotions, but none of them pure unfiltered happiness. It took drugs and an unexpected dance party for Dani to feel something other than pain again, but here she feels it. The only ones who share her emotions? The other women from the Harga. It’s a collective joy. It’s the first time she’s felt part of something bigger than just herself.

After the competition, Dani walks in on Christian cheating on her — by trying to impregnate a girl in a sex ceremony so disturbing that the only natural response is to suppress nervous laughs. She runs from the cabin. She’s trying to escape the crowd so she can grieve alone. Another panic attack is approaching. The rest of the women follow her. They surround her. At first, it seems like they’re terrorizing her by refusing to give her the space she wants. They’re suffocating her as she howls in utter anguish, that guttural scream again. But then they start to mimic her. They match her scream for scream. They’re not doing it for show. They feel what she feels. They have empathy for her. They mirror her emotions. Finally, she’s no longer grieving alone.

Whether or not you like the film comes down whether you buy or sell that scene. If you sell it, the movie is without purpose. The ending isn’t happy; it’s a pointless tragedy where the main character is so low that she ends up joining a murderous cult to find any sense of belonging and helps kill her boyfriend by burning him alive. Sure, he’s a dick who mistakenly thinks he’s a good guy, but even dicks deserve a better fate than getting burned alive while paralyzed inside the belly of a dead bear (told you the movie was fucked up beyond belief). If you buy it, the movie has purpose. The ending isn’t a pointless tragedy; it’s happily ever after. The main character lets go of a crutch. She breaks up with her loser boyfriend. She finds a new family. It doesn’t matter that the family she found is a murderous cult. It doesn’t matter that she breaks up with her loser boyfriend by sentencing him to die in the cruelest of ways. It only matters that she found a family, is free from Christian, and can stand without him.

Midsommar, a meditation on grief, teaches us that healing requires support and help from empathetic friends and family around us. It’s not enough to cry alone. It’s not enough to cry on the shoulder of someone who is only there out of a sense of obligation, not desire. The lengths that Midsommar goes to show this are bizarre, unsettling, and unpleasant — making it a genuine horror movie — but by the end, the overarching message isn’t muddled. Grief is hell. You can’t heal alone. Everyone needs support.

The movie ends with a ceremony. To rid their commune from evil, the Harga must sacrifice nine souls. Josh, Mark, Connie, and Simon are the first four, and their sacrifices have already been made. The next four, coming from within the cult, have already been selected. There’s nothing Dani can do about the eight. Now as the May Queen, Dani is given a choice. She has to pick the ninth sacrifice: a paralyzed Christian or someone already belonging to the cult. She picks Christian. The nine burn — some, like Christian, are still alive when the process begins. They all die. The flames ascend toward the bright summer air. Dani smiles, slowly at first, wide eventually. The movie ends.

Upon arrival, Pelle had explained to Dani and friends that the Harga views life in terms of seasonal cycles. The first 18 years of one’s life in the Harga are considered spring. Ages 18-36 are summer, “a pilgrimage.” Fall, the “working age,” is reserved for ages 36-54. Finally, winter lasts from 54-72, at which point one’s life ends — voluntarily, hence the suicide ceremony they witnessed early on.

The movie begins in the snow of winter, when Dani loses her family to an unfathomable tragedy. Her life as she knows it is over. It ends in the sun of summer, when Dani finds a new family in the most unlikely of places. She’s been reborn. She gets her happily ever after.

As Aster himself put it, Midsommar is “more of a fairytale than a horror film.” It’s just unlike any fairytale you’ve ever seen.