Rogue One is the map Star Wars is looking for

As Disney navigates a treacherous future in a galaxy far, far away, it can look to its first anthology film as a beacon to light the path into the unknown

Star Wars in the Disney era has a thing for maps.

The Force Awakens — Episode VII of a saga that started in 1977 and the first film Disney released in 2015 after purchasing Star Wars for $4 billion in 2012 — opens with Resistance pilot Poe Dameron acquiring a map that he thinks will uncover the whereabouts of Luke Skywalker. The movie ends with the Resistance completing the map and thus, finding Luke. The Rise of Skywalker — the ninth and alleged final film of the Skywalker saga — opens with Kylo Ren trying to find an artifact called a wayfinder that will guide the way to Emperor Palpatine. Over the course of the movie, Rey searches for a wayfinder of her own to find Palpatine. The film’s final act is set up with Rey providing the Resistance with a map to Palpatine.

There’s a subtext to Disney’s reliance on maps that’s difficult to ignore. For as much as Disney has lazily deployed maps as MacGuffins — over four years later, I still don’t understand why a map to Luke Skywalker even exists. Who made it? If no one knows where Luke is and if he doesn’t want to be found, why does a map to his location exist? — Disney is the one in need of a map.

Since acquiring Star Wars, the path forward for Disney has proven to be winding and treacherous. The Force Awakens was the base hit it needed to satisfy both old and new fans, and Rogue One the following year kept its hitting streak alive, but ever since, Star Wars has been mired in controversy, a prolonged replay review that won’t offer an answer that’ll satisfy everyone. The Last Jedi won over critics, but spawned an intense backlash among a portion of fans that clearly bothered Disney judging by the way it proceeded with The Rise of Skywalker, the movie equivalent of a politician trying to please both sides of the aisle by refusing to take a stance. It did not sit well with critics and by Star Wars’ lofty standards, disappointed at the box office. Solo (2018) is better than you remember (or are willing to give it credit for), but Disney botched the timing, releasing it in May instead of Christmas, only five months removed from The Last Jedi hangover and two weeks after Avengers: Infinity War hit theaters. The process has been problematic for most projects, with directors getting replaced before and during production to varying results. The lack of storytelling continuity has been an issue in the sense that there hasn’t really been any. Rian Johnson was handed a separate trilogy the month before The Last Jedi opened, but in the aftermath of the backlash, those plans appear to be on hold as he moves forward with a new unrelated franchise. In May, it was announced that Benioff and Weiss would be working on their own set of Star Wars films, but by October, the once heralded, but now maligned Game of Thrones showrunners walked away from a galaxy far, far away to link up with Netflix. The Mandalorian, Disney’s first live-action television show that debuted with its new streaming service in the fall, was a smashing success (I had my gripes), but the future of Star Wars movies remains murky.

Kevin Feige, who is credited with the meticulous organization and synergy of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, was brought onboard. On Friday, the Hollywood Reporter reported that a new movie is in development via J.D. Dillard and Matt Owens. The rest is unknown. We don’t know if the next movie will be released in theaters or as a Disney+ exclusive. We don’t know if it will be a standalone entry or the beginning of a new saga. We don’t know if it will take place within the framework of Episodes I-IX or in an different corner of the galaxy in an entirely new time period. But by the sound of it, Disney wants to distance itself from the Skywalker saga and carve out its own story. In its own words, it says it is “pursuing a new era in Star Wars storytelling.”

The road ahead is more dangerous than ever before. When Disney bought Star Wars, it was operating safely within the confines of the Skywalker saga. Even when it inevitably fucked up, it still cashed in (The Rise of Skywalker crossed the billion dollar threshold, so let’s not pretend like it was some colossal failure). Now, faced with criticism that it hasn’t done enough to create its own version of Star Wars separate from what George Lucas accomplished decades ago, it sounds like Disney is looking for a map — a wayfinder, if you will — to guide it forward. Luckily for Disney, it already has one, even if it doesn’t already know it.

It’s Rogue One.

Calling Rogue One the map to the future of Star Wars movies should, on the surface, seem paradoxical.

The movie — the first “spinoff” or “anthology film” or “Star Wars story” that was released in December 2016 — only exists to explain a plot hole of A New Hope, the film that started the whole shebang over 42 years ago: Why was Luke Skywalker able to destroy the Death Star with one shot to a conveniently combustable and accessible exhaust port? Its purpose is to turn two sentences from A New Hope’s opening crawl into an entire movie.

“Rebel spaceships, striking from a hidden base, have won their first victory against the evil Galactic Empire. During the battle, Rebel spies managed to steal secret plans to the Empire’s ultimate weapon, the DEATH STAR, an armored space station with enough power to destroy an entire planet.”

It leans on nostalgia more than blink-182 performing What’s My Age Again? in their late 40s. Director Gareth Edwards found a way to incorporate original unused footage from A New Hope 39 years later. The movie flows directly into A New Hope, ending almost exactly where A New Hope begins. There are cameos from characters who appear in A New Hope that serve no other purpose than fan service. Disney even went so far to digitally recreate two main characters, Tarkin and Princess Leia, from A New Hope, giving one of them, Tarkin, a substantial role involving close-ups and lengthy chunks of dialogue even though Peter Cushing, who played the character, died in 1994.

To see how Rogue One is the map to the future of Star Wars, you need to look beyond the surface — past the plot and special effects and Darth Vader’s incredible death march at the end of the film and the messy production process that involved reshoots and a director kinda sorta getting replaced along the way (reportedly, anyways), to the smaller components of the story. Within the larger framework of the story, there exists a map.

The movie about stealing plans is in and of itself a plan. Just look at the characters, the planets and cities they visit, the storytelling methods it deploys, and the standalone nature of the movie.

There seems to be a belief that to grow, Star Wars needs to expand, moving away from the period of time Episodes I-IX, Rogue One, and Solo operate within and starting over in a new part of the galaxy in a different period of time. While moving beyond the Galactic Civil War is inevitable — after all, there’s an entire galaxy “far, far away” and “a long time” to play with, as we’re reminded of seconds before every movie begins — Disney shouldn’t be fleeing it yet. It can, but it doesn’t need to make the jump to lightspeed to a different corner of the galaxy. There are still plenty of stories left to tell in the galaxy we’re familiar with. The stories are just smaller than we’re used to seeing in a Star Wars movie.

You don’t need to look beyond Rogue One’s ensemble cast of characters to see the potential in this type of storytelling approach. All of them — rather, what they represent — could command their own standalone film.

There’s Jyn Erso, the biological daughter of an Imperial scientist and adopted daughter of a Rebel extremist, who’s forced to reckon with their abandonment and their complicated legacies. She’s not Force sensitive. She doesn’t wield a lightsaber. She’s just a soldier who’s disillusioned with the cause and has given up on the idea of ever needing a family. There’s Galen Erso, the Imperial scientist who’s brilliant, but held hostage by the Empire and forced to channel his brilliance into a creation that he knows will cause utter devastating. There’s Lyra Erso, who wants to prevent Galen’s descent into the evil of the Empire. There’s Saw Gerrera, the Rebel who’s broken off from the Rebellion due to his extreme and violent methods of fighting oppression, and is becoming increasingly paranoid in his isolation. There’s Cassian Andor, a Rebel intelligence officer who has killed innocents on behalf of the cause. The cost of his actions weighs on him. There’s K-2SO, an Imperial droid who’s had his identity reprogrammed. There’s Bodhi Rook, an Imperial pilot who defects. There’s Chirrut Imwe and Baze Malbus, both of whom are Guardians of the Whills, but only one of whom is still a believer. There’s Orson Krennic, the Empire’s director of Advanced Weapons Research who confuses peace with terror, but cares more about his own advancement through the ranks than the Empire’s rise across the galaxy. There’s Bor Gullet, an almost pointless creature that definitely should not get its own movie.

Something most of those characters have in common — especially Jyn and Cassian, but definitely not Bor Gullet — is that they’re all morally grey, a feature that is too often lacking in the big stories Star Wars strives to tell. Too often, it’s good vs. evil, light vs. dark, blue vs. red. Too often, the characters don’t feel like real people.

What Disney should be doing is coloring in the galaxy that we already know by telling us the stories of those who are on the peripheries of the main saga. The soldiers who don’t use the Force. The ordinary citizens who are forced to cope with the devastation caused by both the Empire and the war. The workers who keep the Empire humming, but are nothing more than small cogs in a machine who don’t consider the implications of their work. The workers of the Empire who do wrestle with the moral dilemma their jobs pose. The face inside a Stormtrooper’s helmet. The galaxy is more than just Jedis and Siths and Emperors and Senators. There’s an entire war that takes place during the original trilogy that we rarely see. To this point, we’ve mostly only seen the big moments involving the big characters like Luke, Leia, Han, and Chewie. Give us a movie about soldiers in the Rebellion who are fighting in the smaller battles and carrying out the less important operations. Give us a movie about Twilight Company, a book that follows a tight-knit group of soldiers in between the events of A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back — you know, when the actual war is being fought. Give us a real Star Wars war movie. Give us Star Wars’ version of Dunkirk. Give us a movie about the extremists splitting from the Rebellion. Give us a coming of age movie about a boy or girl growing up on a war-torn, Imperial-occupied planet. Give us Lady Bird, but in a galaxy far, far away.

It extends beyond Rogue One’s cast to its locations.

There’s Jedha City, an ancient and holy city, whose citizens are placed in between the might of the Empire’s military and the aggressive desires of a group of freedom fighters.

A small, but important moment in Rogue One comes when the two sides clash in the middle of the city, and Jyn and Cassian are caught in the middle. After spotting a bystander — a toddler — crying out for help, Jyn goes after her, shields her, and hands her off to her mother. We never see them again. The entire Jedha City sequence is one of my favorite parts of the film, because the city feels so alive and authentic. There’s a market with shops and stores and food vendors selling something that looks like calamari. I’d spend an entire movie navigating that city.

There’s Eadu, a miserable looking planet that houses a laboratory. It’s where a group of innocent scientists — well, however innocent anyone working for the Empire can be — are gunned down to make a point. What were the lives of those scientists like? Did they grapple with what they were working to create? Or were they seduced by the importance of their work, even though they knew it’d cause death and destruction throughout the galaxy? Did they even know what they were doing for the Empire?

There’s Scarif, a major Imperial military installation in a tropical paradise. What kind of lives do the stormtroopers and officers stationed there live?

I don’t mean to say Disney should make movies about those specific places or individuals — that said, they’ve already green-lit a live-action show about Cassian, and if they weren’t absolute cowards, they’d also give Jyn her own show starring Felicity Jones, who has made it clear that she’d like to return to the character. But those specific individuals represent the stories Star Wars should be telling. We already know the fate of the galaxy. But we don’t know about the more ordinary people who make up the galaxy. By filling in the details, the story that has already been told in Episodes I-IX wouldn’t change, but it would be made more impactful, because we’d actually know who the Rebellion/Resistance were fighting for and against. I guess what I’m saying is that instead of switching the setting, Disney should stay in the same sandbox, but narrow the focus and scope. Every story doesn’t need to put the fate of the galaxy on the line. The stakes can shrink. They can be about an individual who doesn’t hold the key to the galaxy in the palm of their hand. They can be about someone just trying to live.

Finn, from Episodes VII-IX, is a good example of this. He’s a stormtrooper, FN-2187, who was conscripted at childhood. Now, as a adult, he doesn’t want to be a stormtrooper. He defects in the opening minutes of Episode VII. That alone is enough to form the basis of an entire film. But due to the presence of Rey and Kylo, the two beating hearts of the sequel trilogy, and the overarching stakes of the trilogy (save the galaxy!), Finn is a side character. By Episode IX, he’s reduced to doing nothing more than a person who screams “REY!” whenever he sees that she’s in harm’s way. He’s basically us in the audience if we could yell freely without getting shushed or having popcorn thrown in our face — or in my case, listening to my upstairs neighbor stomp angrily on his floor / my ceiling.

There’s no room for a story about one turncoat stormtrooper when the fate of the galaxy is at stake. The sequel trilogy introduced and flirted with these ideas, but couldn’t commit to them.

After 42 years, Star Wars has already told the larger story. Now, it’s time to fill in the details by giving those types of people their own standalone films. Everything doesn’t have to be a trilogy. Star Wars movies can have a beginning, middle, and end that doesn’t set up the next episode.

Rogue One is “a Star Wars story”. It’s right there in the title: Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. For obvious reasons, I’ve declined to use its full name until this point.

The title isn’t important, but what it represents is. It’s one story. Singular. It has a beginning, middle, and end. Yes, Rogue One is able to cheat by leading directly into A New Hope — in that sense, it’s more like a prequel — but the singular nature of the movie is a strength.

It makes the stakes more real. When you watch the sequel trilogy, you don’t watch thinking that Rey, Kylo, or Finn might die in Episodes VII or VIII. It’s not until Episode IX that you think it could, in theory, happen. Even then, they refused to commit to killing Chewie because of his importance to generations of Star Wars fans, even though it would’ve been a far more audacious and interesting storytelling decision to have had Rey accidentally kill Chewie with her newfound power that we previously only associated with the darkest of evils. When you watch Rogue One, the stakes feel real. You know Jyn and Cassian and K-2SO and Baze and Chirrut aren’t in the original trilogy. You know they don’t play a role in the story that’s already been told. So, you know they might die. It elevates the tension. When they eventually do die, it makes their contributions to the cause matter more. It adds more emotional weight to the rest of the story.

I loved Rogue One because it was the first time the war part of Star Wars felt real. Usually characters have sequel and merchandise insurance. Things can’t get real until the finale. But every standalone movie is a finale. They’re all real.

I saw Rogue One in theaters a dozen times. That’s not a figure of speech. I literally went to see it in theaters on 12 separate occasions — and this was before I had MoviePass or A-List.

When people hear how many times I paid to see the same movie, they assume two things:

I’m crazy (true).

I kept going back because of the third act, when arguably the best space battle in the entire saga takes place and Vader is finally unleashed like we’ve never seen before.

Something I realized along the way was that it wasn’t the big, epic moments that kept me coming back. It’s the smaller, quieter, human-er moments that I’m addicted to.

Rogue One is the only Disney-era Star Wars movie that doesn’t begin with a bang. There’s no shootout (The Force Awakens), massive space battle (The Last Jedi), chase sequence (Solo), or lightsaber action / chase sequence (The Rise of Skywalker). Rogue One starts with conversations: a mom and dad saying goodbye to their daughter, a protective father and husband trying to sell a lie to a dangerous man, and an equally protective mother and wife directly confronting that dangerous man. It’s them, in an open field, talking. It’s haunting, listening to them argue about the subtle differences between peace vs. terror, hostages vs. heroes. There aren’t any red vs. blue lightsaber fights, because Rogue One is trying to convey the nuances of Star Wars that so many of the trilogy films lack. It’s not always as simple as good vs. evil, light vs. dark, red vs. blue. Sometimes it’s degrees of gray pitted against each other.

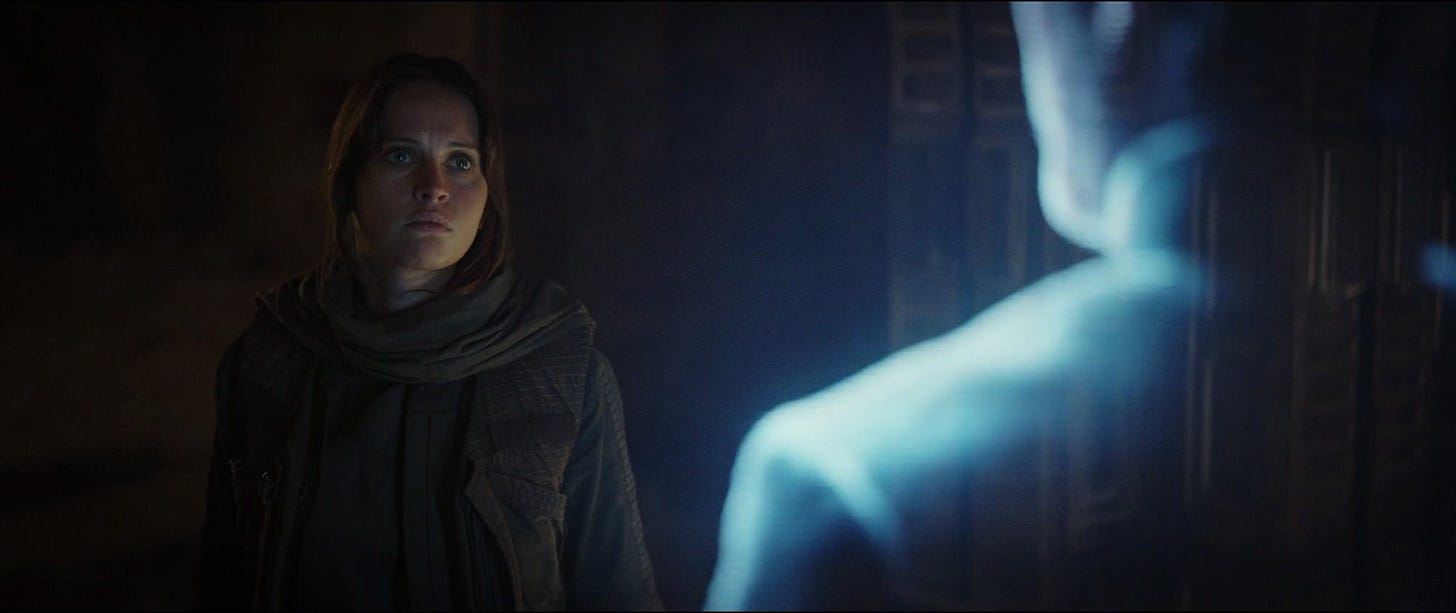

The scenes I always come back to are the quieter moments. Galen’s hologram message to Jyn might be my favorite moment in all of Star Wars, the blue hue of the hologram flickering across her face as she’s forced to reconsider the grudge she’s held against her father and reckon with the consequences of his message. He’s standing right there in front of her for the first time since the opening scene of the movie, but he’s not there, not really. She’s the closest she’s been to him in 15 years, but she’s just as far away as before. It’s a father explaining to his daughter why he abandoned her and went back to work for the Empire while her adoptive father looks on after he just got done explaining to her why he also had to abandon her.

It’s the most poignant moment Star Wars has put on screen, because it’s the most fundamentally human moment in Star Wars — more so than Vader’s reveal to Luke that he’s his father, which was more of a plot twist than a hammer to the heart.

“Saw, if you’re watching this, then perhaps there is a chance to save the Alliance. Perhaps there’s a chance to explain myself and, though I don’t dare hope for too much, a chance for Jyn, if she’s alive, if you can possibly find her to let her know that my love for her has never faded and how desperately I’ve missed her.

“Jyn, my Stardust, I can’t imagine what you think of me. When I was taken, I faced some bitter truths. I was told that, soon enough, Krennic would have you as well. As time went by, I knew that you were either dead or so well hidden that he would never find you. I knew if I refused to work, if I took my own life, it would only be a matter of time before Krennic realized he no longer needed me to complete the project. So I did the one thing that nobody expected: I lied. I learned to lie. I played the part of a beaten man resigned to the sanctuary of his work. I made myself indispensable, and all the while I laid the groundwork of my revenge. We call it the Death Star. There is no better name. And the day is coming soon when it will be unleashed. I’ve placed a weakness deep within the system. A flaw so small and powerful, they’ll never find it.

“But, Jyn. Jyn, if you’re listening, my beloved, so much of my life has been wasted. I try to think of you only in the moments when I’m strong, because the pain of not having you with me, your mother, our family, the pain of that loss is so overwhelming I risk failing even now. It’s just so hard not to think of you. Think of where you are. My Stardust.”

The most important moment of the movie might be an argument — verbal, not physical — between Jyn and Cassian, when she accuses him of blindly following orders, and he accuses her of latching onto a galaxy-wide cause for selfish reasons. It’s two complex, neither entirely good nor bad soldiers arguing about the complexities of warfare and the consequences of decisions that lack a clear right or wrong answer.

Cassian: “I had orders, orders that I disobeyed. But you wouldn’t understand that.”

Jyn: “Orders, when you know they’re wrong? You might as well be a stormtrooper.”

Cassian: “What do you know? We don’t all have the luxury of deciding when and where we want to care about something. Suddenly the Rebellion is real for you. Some of us live it. I’ve been in this fight since I was six years old. You’re not the only one who lost everything. Some of us just decided to do something about it.”

Jyn: “You can’t talk your way around this.”

Cassian: “I don’t have to.”

I’m not suggesting that Rogue One is the only Star Wars movie to do this. Part of the reason The Last Jedi is the best sequel trilogy film and will age better than The Force Awakens and The Rise of Skywalker is because Rian Johnson understood the most interesting dynamic of those movies is the complicated relationship between Rey and Kylo, two young adults who are torn between the light and darkside of the Force. Even though Rey and Kylo were seldom in the same location, Johnson figured out a way to feature the two of them talking to each other without explosions or lightsaber duels or background noise. The most interesting moments of that movie are when they’re just talking and sifting through their mixed emotions.

The Rise of Skywalker failed to understand this. It understood that Rey and Kylo’s ForceTime sessions worked. But it didn’t understand why it worked, which is why in The Rise of Skywalker, Rey and Kylo continue their ForceTime sessions, but do it in much louder ways; they spend one of their sessions having a lightsaber duel.

I saw The Rise of Skywalker four times in theaters. So, I liked the movie. But I didn’t love it — not because of any of the larger story choices, but because there’s rarely any moments when the characters are allowed to talk and breathe. It’s all zip and blast. There’s never any moments, at least until the very end, to stop and consider the impact of all that zipping and blasting.

Star Wars would be wise to heed the advice Luke gives Rey near the beginning of The Last Jedi.

“Breathe,” he says. “Just breathe.”

It’s the smaller moments, the human interactions, that hold up on a second, third, fourth and 12th viewing. Those are the moments Star Wars should be chasing.

Luckily, Disney doesn’t have to look far to find them. There’s no need to go rogue.

It already has a map, a lightsaber illuminating a pitch black night, the gentle blue hue of a hologram dancing across the face of someone to lift them out of the darkness of their own despair and to awaken the light buried deep within them.

Good stuff. Part of what I believe makes “Star Wars” so beloved is its ability to entertainingly and emotively tell a good-and-evil story, but I think you articulated part of the problem of having that story get so grand in scope and scale: You lose the human emotion of it. So while I maintain “Star Wars” should be a place where we get the clear-cut morality of dueling sides, I also agree the original trilogy already did that well, and that we’ve recently gotten some of the best character/human work when the stories/characters have been more more “grey.” Great points about the difference between the “ForceTimes” in 8 and 9; had never thought of it that way.

This was incredibly in depth. Love your writing man.