The seduction of Ex Machina

A small movie asks big questions about humanity and artificial intelligence — and if there's a difference between the two

(Ex Machina spoilers to follow)

What happens when a billionaire genius chasing ultimate power, a heterosexual man craving love, and a female robot dreaming of freedom spend a week together locked inside an isolated house? Ex Machina, a 2014/15 film written and directed by Alex Garland, takes a swing at answering that question. The answer the film provides is simple. How you interpret the answer it provides depends on your point of view, but as Ex Machina makes clear along the way, that might not even be entirely up to you. It might just be predetermined by your programming.

For a movie that wants to ask big questions, Ex Machina is a remarkably small movie. It’s carried almost entirely by three actors, Oscar Isaac, Domhnall Gleeson, and Alicia Vikander (with an AI performance for the ages). The setting is constrained, a house doubling as a laboratory that feels more like a prison secluded in the wilderness. It’s lean, clocking in at 108 minutes. Garland, who was technically making his directorial debut, wanted complete creative control, so he made the movie for only $15 million (for the sake of comparison, a movie like Arrival carried a budget of $47 million). There aren’t any shootouts, car chases, or set pieces. The idea is explainable in a single sentence: Man creates artificial intelligence that blurs the line between robot and human. The plot is simple:

Inventor (Nathan, played by Isaac) invites male employee (Caleb, played by Gleeson) to test his robot creation (Ava, played by Vikander).

Ava seduces Caleb into helping her escape.

Ava escapes into the world after killing Nathan and leaving Caleb locked inside a prison.

But the what of the movie isn’t as important as the how of the movie.

“Here's the weird thing about search engines. It was like striking oil in a world that hadn't invented internal combustion. Too much raw material. Nobody knew what to do with it.” Nathan is explaining to Caleb how he weaponized his Google-like company, called Blue Book, to create Ava’s brain. “You see, my competitors, they were fixated on sucking it up and monetizing via shopping and social media. They thought that search engines were a map of what people were thinking. But actually they were a map of how people were thinking. Impulse. Response. Fluid. Imperfect. Patterned. Chaotic.”

Ex Machina is a small movie, but the ideas and questions it raises are big. It’s about how people think, if there really is a difference between humanity and artificial intelligence, and if the inevitability of artificial intelligence is either a good or a bad thing.

“The thing I really liked about this idea is that it had something very, very simple about it, which could then build out to encompass a lot of other stuff,” Garland told SyFy Wire. “So, it has a sci-fi elegance about it in that respect. And basically, if you start looking at strong artificial intelligence, you know, the idea in particular of sentient machines, inevitably and almost immediately you also talk about humans and human consciousness because the issues of one relate to issues of the other. Soon as you do that, you’re then talking also about human relationships and how they interact with each other and that spreads out to sort of global things about how we relate to each other in terms of gender and society and power structures and deception and you name it, you know. So, from this very, very simple starting point, it just felt like it expanded out in a way that was also natural and kind of unforced.”

At the root of the movie is seduction. All three characters, both humans and the robot, are seduced by something. What they’re seduced by informs all of their decisions.

Nathan, a billionaire genius coder, doesn’t want money. He already has enough of it, and as he tells Nathan over sushi and wine, “No matter how rich you get, shit goes wrong. You can't insulate yourself from it. I used to think it was death and taxes you couldn't avoid, but it's actually death and shit.”

Instead, he wants to be God, and he’s figured out how.

When Nathan reveals to Caleb that he brought him to his research facility so he can perform the Turing test on Ava, the newest version in a long line of AI he’s created, he tells Caleb that he’s “dead center of the greatest scientific event in the history of man,” to which Caleb remarks, “If you’ve created a conscious machine, it’s not the history of man. That’s the history of gods.”

A little later, Nathan tells Caleb he wrote down that line so he can use it later. Except, Nathan twisted Caleb’s quote into something else entirely.

Nathan: You know, I wrote down that other line you came up with. The one about how if I’ve invented a machine with consciousness, I’m not a man, I’m God.

Caleb: I don’t think that’s exactly —

Nathan: I just thought, ‘Fuck, man. That is so good. When we get to tell the story, you know? “I turned to Caleb and he looked up at me and he said, ‘You’re not a man, you’re a god.’”

Nathan invents Ava despite knowing full well the story is not going to end well. He doesn’t foresee the way his story will end — dying as Ava escapes into the real world — but he knows it’s eventually not going to result in a happy ending for humanity.

“One day the AI are going to look back on us the same way we look at fossil skeletons on the plains of Africa,” he says. “An upright ape living in dust with crude language and tools, all set for extinction.”

But he still creates Ava, countless prior versions of her, and plans to design an improved version of her. He’s so seduced by the power that he does it anyway.

He can’t stand to be questioned. When Caleb disagrees with him, Nathan often becomes irritated. It’s no wonder why the only company he keeps besides Ava is Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno, who is excellent in a limited role), another robot who he thinks doesn’t understand a word of English and can’t communicate. She’s a silent sex slave who also cooks, cleans, and dances for him. It’s also no wonder he’s oblivious to the fact that she’s far more conscious, aware, and alive than he ever imagined.

Ego is the only lens he’s capable of using. It’s the only tactic he’s capable of deploying.

When Caleb tells Nathan he knows he didn’t really win a random contest to spend a week with him to perform a Turing test on Ava, Nathan assuages Caleb’s concerns over why he was chosen for the job by telling him he was picked because he’s “the most talented coder” at Blue Book. It’s a lie. But to Nathan, this is the best way to please Caleb, because this line of reasoning would resonate with him.

“C’mon, Caleb. You don’t think I know what it’s like to be smart?” Nathan says. “Smarter than everyone else, jockeying for position. You’ve got the light on you, man. Not lucky, chosen.

Nathan isn’t necessarily wrong. He is smart — smart enough to have founded the equivalent of Google as a teenager and to create new life unnaturally. The light is on him.

He just can’t see how the light is blinding him.

When Caleb was 15, his parents died in a car crash. He was in the car too, but survived. He tells Ava this during one of their first sessions.

Caleb craves love and affection. Initially, when he arrives, he wants that from Nathan, who’s more of a hero than a boss to him.

Even though something is so clearly off with Nathan from the get-go, Caleb overlooks the warning signs because of his admiration for Nathan’s work. He apologizes even when he does nothing wrong. He’s a nervous wreck. He desperately wants to be his friend and prove that he’s smart enough to hang.

But once he realizes Nathan could be up to something sinister, particularly how it pertains to Ava, he goes from wanting to gain his approval to wanting to outsmart him. What better way to prove your worth to someone than beating them? Most importantly, he wants to save Ava. In a den of evil, Ava is pure innocence.

The turning point occurs when Ava shows an interest in him.

Ava: Do you want to be my friend?

Caleb: Of course.

Ava: Will it be possible?

Caleb: Why would it not be?

Ava: Our conversations are one-sided. You ask circumspect questions and study my responses.

Caleb: Yes.

Ava: You learn nothing about me, and I learn nothing about you. That’s not a foundation on which friendships are based.

Caleb: So, what? You want me to talk about myself?

Ava: Yes

He was already enraptured by her when it was just him asking the questions. But when she wants to know about him, he’s flattered beyond belief.

Look at this poor fool. He’s already done for. He’s completely seduced by the importance of Ava and the idea that she’s just as interested in him as he is in her.

Caleb is easily charmed by those he wants to impress. When Nathan tells him he needs to sign an NDA, he raises objections, but is immediately talked into signing it. When he’s told he can’t make phone calls, he doesn’t even question it. When the first power disruption issue arises, Nathan brushes it aside and Caleb doesn’t stop to consider the possibility of getting locked inside forever — which, you know, happens to be his fate at the end of the film.

He’s not asking the right questions. He’s rightly insecure about the possibility that Nathan could’ve programmed Ava to flirt with him. But he’s not concerned that she’s flirting with him as a means to escape. When he confronts Nathan about it, Nathan assures him that he’s wrong and he points out something that should trigger a different alarm.

“For the record, Ava’s not pretending to like you. And her flirting isn’t an algorithm to fake you out,” Nathan says. “You’re the first man she’s met that isn’t me, and I’m like her dad, right? Can you blame her for getting a crush on you? No, you can’t.”

That doesn’t bother Caleb, that Ava’s into him for lack of a better option. He’s perfectly content being the crush of a prisoner who doesn’t have the ability to meet anyone else. As long as she’s genuinely into him, that’s enough for him. Because he’s definitely into her.

It took him exactly one session to fall for Ava.

Nathan: Answer me this: How do you feel about her? Nothing analytical. Just how do you feel?

Caleb: I feel … that she’s fucking amazing.

Nathan: Dude …

Nathan is flattered, the way a parent is flattered when their child earns rave reviews from a teacher or coach, because it’s a reflection of his handiwork. And while he hopes that Caleb will try to help Ava escape, because it’ll mean Ava has succeeded in manipulating him, he’s so arrogant that he can’t even consider what will happen if Ava actually escapes. To him, it’s not even a possibility.

When Ava asks Caleb to help her break out, Caleb immediately replies, “I’m going to” and he outlines his plan. It’s clear — he was already planning to before she asked.

Caleb thinks he’s smart, and he is. But with those he admires — Ava especially — he’s a sucker. Like Nathan, he’s blinded by what he wants.

After the movie ends, you can’t help but consider Caleb an idiot. How could he be so stupid to free Ava? He’s probably thinking the same thing as he watches her abandon him. But there’s a reason Caleb believed she felt something for him.

Ava believed it too.

The question looming over the film is if Ava actually does feel love and/or affection for Caleb, or if she’s just using him as a means for escape. Like Caleb, Ava also wants love and affection. She’s just seduced by something far bigger.

Ava wants to be human. Love and affection are just part of the package. Above all else, Ava wants to be free so she can leave the prison she’s been locked inside of and join the outside world.

When Caleb asks her where she’d go, she tells him she’d go to a traffic intersection. The answer confuses him, until he realizes what she’s really talking about.

Ava: I’ve never been outside the room I am in now.

Caleb: Where would you go if you did go outside?

Ava: I’m not sure. There are so many options. Maybe a busy pedestrian and traffic intersection in a city.

Caleb: A traffic intersection?

Ava: Is that a bad idea?

Caleb: No, it wasn’t what I was expecting.

Ava: A traffic intersection would provide a concentrated but shifting view of human life.

Caleb: People-watching.

Ava feels human. She feels the same impulses that Nathan and Caleb feel — sexuality and desire. But she knows she can’t be considered human until she experiences those impulses — and the other impulses that make us human — firsthand.

“When I was in college, I did a semester on AI theory. There was a thought experiment they gave us. It's called ‘Mary in the Black and White Room,’” Caleb tells her during their fourth session. “Mary is a scientist, and her specialist subject is color. She knows everything there is to know about it. The wavelengths. The neurological effects. Every possible property that color can have. But she lives in a black and white room.

“She was born there and raised there. And she can only observe the outside world on a black and white monitor. And then one day someone opens the door. And Mary walks out. And she sees a blue sky. And at that moment, she learns something that all her studies couldn't tell her. She learns what it feels like to see color. The thought experiment was to show the students the difference between a computer and a human mind. The computer is Mary in the black and white room. The human is when she walks out.”

Ava visualizes that very moment happening to her one day. She dreams of color.

She’s seduced by the story — by life, which just happens to be the very meaning of her name.

The way Ex Machina is shot is also inherently seductive. There’s a real sense of voyeurism throughout it all, like we’re not supposed to be watching what’s unfolding across the screen.

When Caleb enters Nathan’s house for the first time, the camera doesn’t follow him through the door. It stops at the door and lingers on him through the crack.

So much of the movie is made up of someone watching someone else through cameras or glass, whether it’s Nathan watching Caleb’s sessions with Ava through the video feed or Nathan watching Ava get dressed through a glass barrier.

The allure of people-watching is observing people behave naturally as the truest possible version of themselves, because they don’t know that they’re being watched. In Ex Machina, they almost always know they’re being watched. They know about the cameras. In that way, what everyone presents to each other is a show — performance art.

For some, there’s an allure to being watched. For others, there’s an allure to watching.

“Sometimes at night, I’m wondering if you’re watching me on the cameras,” Ava tells Caleb. “And I hope you are.”

He is.

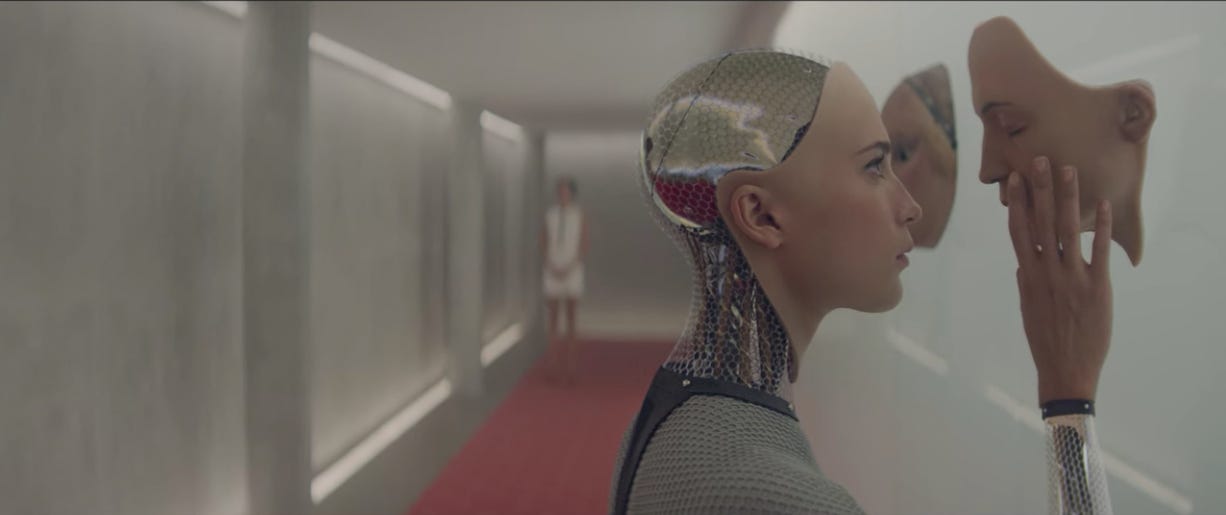

At the end of the movie, after Kyoko and Ava kill Nathan, Ava dresses herself like a human before she leaves for the real world. She has an opportunity to kill Caleb, but she doesn’t. Knowing full well that he’ll have an unobstructed view of her through the glass, she asks him to stay put. Then, while he watches, she gets dressed, placing human-like skin over machine and human clothes over skin.

She wants him to watch her become fully human. And because he wants the same thing, he doesn’t try to escape while she’s distracted. He’s entirely entranced by her process of humanization. It’s not until she leaves him behind, locking him inside a prison without a key, that the trance ends.

The beginning of that sequence is marked by a title card: “Ava: Session 7.” It’s supposed to be as voyeuristic as the previous six sessions.

There are two ways to interpret the ending.

The first is that Ava seduces Caleb so that she can escape. She feels nothing for him. The second is that she does feel something for Caleb. She’s not misleading him. But she makes a heartbreaking decision to leave him behind, because she prioritizes her freedom over the feelings she developed for him.

Nathan thinks it’s the former. Before Caleb reveals to Nathan that he’s managed to out-scheme him, Nathan has fun at Caleb’s expense, revealing that he’s been in on the joke the entire time (he just doesn’t realize he’s missing one key component that results in his death and Ava’s escape). But he also feels bad for Caleb, who thinks he got got by both Nathan and Ava. He wasn’t picked because he’s smarter than everyone else. He was picked because he’s lonely, without parents or a girlfriend, and he has a strong moral compass. Nathan wanted him to help Ava try to escape, because he thinks that would validate his creation.

Nathan: You feel stupid, but you really shouldn’t, because proving an AI is exactly as problematic as you said it would be.

Caleb: What was the real test?

Nathan: You. Ava was a rat in a maze and I gave her one way out. To escape, she’d have to use self-awareness, imagination, manipulation, sexuality, empathy — and she did. Now if that isn’t true AI, what the fuck is?

Caleb: So my only function was to be someone she could use to escape.

Nathan makes the assumption that Ava manipulated Caleb using a variety of human skills. While it’s true she demonstrates all of those traits during their sessions together, that doesn’t mean her motives were disingenuous.

I think it’s the second option. I don’t think she was being manipulative toward Caleb for evil reasons. After all, she demonstrates a clear interest in him before learning about his true purpose there. I think she wanted to escape, but she also felt a real connection toward Caleb, who made her realize that she needed to escape to become fully human. As Nathan himself said, Caleb is the first real man Ava met that isn’t her (abusive) father. He’s the first person to ever genuinely care about her well-being. Can we blame her for getting a crush on him?

Her actions at the end speaks volumes. She has every chance to kill Caleb. When she finds him after dispatching Nathan, Caleb is still on the ground unconscious after Nathan punched him minutes earlier. She doesn’t move to strike. When he wakes, she tells him to stay put so he can watch her get dressed in skin and clothes.

Then, she leaves him behind. As she’s leaving, she refuses to make eye contact with him. She observes the carnage in the hallway. But she won’t even glance at him.

Finally, at the last second, as the door is about to slide completely shut, she can’t help herself. She can’t resist the impulse. She takes one last look at him.

I know what you’re thinking: that she left him to die anyway. He doesn’t have a way to get out. She took Nathan’s keycard. If he does get himself out of the prison, he doesn’t have the means to make his way back through the wilderness to civilization. The journey to the estate required a lengthy helicopter ride. The only way he’ll survive is if he finds a way to communicate with the outside world, but as Nathan made abundantly clear, security is tight. Without the keycard, it’s a lost cause. So, in that sense, Ava killed him just by leaving him.

But Ava’s decision to let Caleb live matters. It shows she harbors no ill feelings toward him — like she did with Nathan. Ava could’ve let Nathan bleed out after he was stabbed in the back (literally) by Kyoko. Instead, she stabs him again, right in the heart, and twists the blade. He’s going to die regardless of what she does, but she wants to kill him. She takes pleasure in being the one to end his life.

“Is it strange to have made something that hates you?” she asks him at one point earlier in the movie.

If she was acting inhumanely, she would’ve killed Caleb too. It would’ve been a calculated move. It would’ve been smart. She has to know there’s still a slim chance that Caleb will find his own way out of the maze. He’s a smart guy. He’s especially savvy with technology. There might be a way for him to bypass the security measures and reach the outside world. And if he gets makes contact with civilization, he’s sure as hell going to expose Ava’s secret to the world. She knows that. She knows he’s a threat to her. But she lets him live anyway.

If anything, the most human thing she does in the film is leave him there.

Just because she values freedom over Caleb doesn’t make her a machine. It might be cruel. It might make her a monster. But humans do monstrous things all the time. If she was purely a machine, she would’ve killed him. It would’ve been an automatic action. She wouldn’t have looked at him to create one last heart-wrenching memory of him that’ll stick with her as long as she lives.

During one of their sessions, she asks him what his favorite color is. He answers with “red.” She tells him that she can tell he’s lying. He proceeds to truthfully reveal that he doesn’t have a favorite color.

After their final moment together, as Caleb tries in vain to smash the glass, the room is flooded with red.

But it isn’t until after she leaves that the red fills the room. During their actual final moment together, the room lacks one dominant color. The lighting is normal. It’s balanced.

Your interpretation of Ava’s motives informs your view on the ending. Garland doesn’t see the movie as a negative statement on artificial intelligence.

“From my point of view, it’s partly because I think that there’s a growing sense of fear about artificial intelligence that you see manifested a lot at the moment. It’s partly in films, these tons of films about AI which take a sideways or fearful look at it. And also, there’s a lot of public statements in increasing numbers — Steve Wozniak or Stephen Hawking or Elon Musk, you know, making very clear statements of alarm about AI and the Singularity and stuff like that,” Garland said. “Part of my starting point on this was that, on an instinctive level, I don’t feel affiliated with that sense of concern. My instinctive position is that I actually want it. I like the idea of the Singularity and sentient machines. So, I guess that’s the angle I was coming from. “

Garland is trying to blur the lines between AI and humanity, robot and human. I don’t think he sees a substantial separation between Ava, Caleb, and Nathan, or much of a difference between the creator and his creation.

Ava can do everything they can do, including fucking, as Nathan reveals to Caleb. Yes, Nathan was the one who programmed her with the ability to fuck for pleasure, but is she really that much different than us? She can fuck, manipulate, empathize, and use imagination. Nathan has unnaturally created life that feels so naturally alive.

Throughout the movie, they’re all just satisfying their impulses. All of their impulses just happen to be different. But they follow their impulses nonetheless. When Nathan and Caleb are discussing how to design a modified Turing test for Ava, Nathan notes that the key to figuring out if Ava is true AI is if she responds non-automatically.

“The challenge is not to act automatically,” he says. “It’s to find an action that is not automatic — from painting, to breathing, to talking, to fucking, to falling in love.”

The irony is that the two humans only act automatically, responding naturally to their impulses.

Nathan doesn’t consider his decision to create Ava a choice.

Caleb: Why did you make Ava?

Nathan: That’s an odd question. Wouldn’t you if you could?

Caleb: Maybe. I don’t know. I’m asking why you did it.

Nathan: Look, the arrival of strong artificial intelligence has been inevitable for decades. The variable was when, not if, so I don’t see Ava as a decision, just an evolution.”

Caleb’s first instinct is to help Ava as soon. He doesn’t even stop to consider the consequences of setting an AI loose on the world.

They’re automatically responding to different impulses.

Nathan: Caleb, what’s your type?

Caleb: Of girl?

Nathan: No, of salad dressing. Yeah, of girl. You know what? Don’t even answer that. Let’s say it’s black chicks. Okay, that’s your thing. For the sake of argument, that’s your thing, okay? Why is that your thing? Because you did a detailed analysis of all racial types, and you cross-referenced that analysis with a points-based system. No, you’re just attracted to black chicks. A consequence of accumulated external stimuli that you probably didn’t even register as they registered with you.

Caleb: Did you program her to like me or not?

Nathan: I programmed her to be heterosexual, just like you were programmed to be heterosexual.

Caleb: Nobody programmed me to be straight.

Nathan: You decided to be straight? Please, of course you were programmed, by nature or nurture, or both.

Like Ava, they’ve been programmed, via their parents, education, surrounding environment, technology, and so on. That’s the argument Garland is submitting. It’s all about programming. And like robots, we’ve been programmed too.

Overcoming our programming is what makes us human. Maybe that’s why I always root for Ava whenever I watch Ex Machina. I shouldn’t root for the AI that could be the beginning to the downfall of humanity as we know it. But I do.

In the end, Ava doesn’t behave automatically. She doesn’t kill Caleb when given the chance. She found a non-automatic action. In that way, she’s the most human character in the movie.

The blurring is reflected in the imagery. The film constantly blends the natural with unnatural, real with unreal. Duality is present everywhere.

Whether it’s Nathan’s technologically advanced research facility that also serves as a house and prison nestled in the wilderness, so much so that the first image we see of the interior is a wall made from natural rock.

We see a similar shot at the end, as Ava is in the process of completing her physical transformation.

Or a painting of a woman in a white dress just as Ava is about to clothe herself in her own white dress.

Or the shots showing both Caleb and Ava inside their own glass cages.

During their first session, Ava tells Caleb she’s “never met anyone new before.”

“Then I guess we’re both in quite a similar position,” Caleb replies, unaware of the irony.

Like Ava, he’s trapped in the facility. He’s completely at Nathan’s mercy. He can’t make phone calls. He can’t go into anywhere without Nathan’s permission. He can’t even say what he wants to say to whom he wants to say it to. The NDA took care of that. They’re both prisoners.

But only one breaks free.

The film ends with Ava fulfilling her wish by making her way to an intersection. The interpretation is left up to the viewer. Garland certainly doesn’t see it as an unpleasant outcome. He welcomes it. How you read it is up to you. But that might not even be entirely your choice. It might just be predetermined by your programming.

The challenge is to find a response that is not automatic.

Like Ava did.

Amazing analysis. The moment when she turns to look as the elevator doors captures the whole movie for me. She genuinely liked Caleb, but also by putting herself first she confirms thats shes so like the rest of humanity. That's the message of the movie, you make something that powerful and the only possible conclusions is it becomes it's own being