The staying power of Arrival

An ode to Denis Villeneuve's science fiction masterpiece of 2016, a movie that has the traits to live on well past its date of arrival

(This post contains spoilers for Arrival)

Rewatching movies is a lot like understanding the Heptapods’ written language. Once you understand it, you know how everything ends even before the ending arrives. You’re watching the beginning again, but you’re not watching it the way beginnings are intended to be watched. You’re watching it unfold, but with the ending burrowed in your mind, so that you can see how the pieces fall into place instead of only looking at the puzzle upon completion. When the ending comes, it doesn’t arrive as a surprise, but as an ending you’ve seen coming for two hours. But you watch it again anyway. You embrace the journey. You welcome every moment of it.

I rewatch movies a lot. Arrival especially so. I saw it twice in theaters, bought it on blu-ray when it was released, and have rewatched it countless times since — once in August with my dad and again last week when I decided I wanted to write on it. After my dad and I finished, he asked me why I kept revisiting the movie.

I didn’t have a good answer for him — at least I wasn’t able to convey it effectively. It almost felt like I was Abbott and Costello — the two alien Heptapods sent to Montana to deal with the Americans — trying to communicate with Dr. Louise Banks, an American linguist, and Ian Donnelly, an American physicist. It’s probably my favorite movie (not named Rogue One) ever, but it’s not easy to explain why.

At one point in the film, Ian remarks that the Heptapods write the beginning and ending of their thoughts all at once. They don’t start at the beginning and end at the end. All of it comes out in a single moment.

"Imagine you wanted to write a sentence using two hands starting from either side,” Ian says. “You would have to know each word you wanted to use, as well as much space they would occupy. A Heptapod can write a complex sentence in two seconds, effortlessly.”

I’ll be honest. This story won’t be like that. Seven months after my dad asked me what it was about Arrival that kept me coming back, I still don’t have a clear and concise answer to a simple question.

Arrival, directed by the great Denis Villeneuve and based on Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life, is a big movie. It’s about aliens coming to Earth to save humanity and themselves. Twelve vessels arrive around the world. One hovers above Montana. Louise and Ian are tasked with figuring out why the Heptapods have come to our planet before they annihilate us or the natural instincts of the militaristic governments around the globe kick in and attempt to blast the aliens to smithereens.

In that sense, it’s not a wholly original movie. Aliens coming to Earth will never be a unique movie concept. But the way Arrival approaches their arrival is unique to most movies. Most alien movies aren’t this quiet.

As Amy Nicholson, writing for MTV, noted at the time:

The moments that change our lives can land with a hush. We panic and fret and cry about what might be, and then when the unthinkable finally happens, the air goes still, like you missed your own death and woke up in the tomb. Movies — especially sci-fi movies like Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival — tend to get this wrong. They think every big moment is big, that when the aliens land, our heads will pound with lasers and explosions and a crashing orchestra. But Villeneuve (Prisoners, Enemy, Sicario) taps into that uncanny quiet. Here, the aliens are announced the same way many of my college classmates found out about 9/11. Linguistics professor Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) walks into her lecture hall and most of her students are gone. A text message chirps, and then another, tiny squawks alerting us that the climate has changed.

We tend to associate aliens with war and science fiction studio films with action. Generations of science fiction stories have told us that when aliens provide an answer to The Question (are we alone in the universe?), they’ll do so violently. Most alien movies are really war movies, swapping out Nazis for aliens. In Arrival, the only fighting that transpires is between humans. The only gunshots fired are in the backdrop between American soldiers. The only explosion that threatens Louise and Ian is a bomb set by rogue American soldiers.

The Heptapods don’t come to Earth for sinister purposes. They want to save us and themselves. Throughout the movie, we just can’t get out of our own damn way to let them help.

Louise: “Many become one” could be their way of saying “some assembly required.”

CIA Idiot: Why hand it out to us in pieces? Why not give it all over?

Louise: What better way to force us to work together for once?

It resonates because it certainly feels like that’s the way it will inevitably end for us, through our own devices. Like all good science fiction stories, Arrival tells us more about ourselves than aliens. Countless movies have told us how we’d handle an alien invasion (triumphantly through combat). Arrival tells us that we might struggle more with aliens if they pay us a visit, but don’t attack.

It’s rare for a studio science fiction film to be so quiet, but that’s probably because it’s not really a studio film. Technically, Paramount distributed the movie, but as the movie’s writer, Eric Heisserer, explained during a Reddit AMA, the studio didn’t necessarily involve itself in the actual making of the movie.

“I can confess a key bit: This wasn't a studio film,” he wrote. “It was acquired, for sure, but we made it largely independently. No studio wanted to risk making the film as it was, not until they felt assured it would work (and having Denis and Amy on board certainly did that).”

Ironically enough, Arrival was severely impacted by a studio science fiction film. Speaking with Collider, Heisserer explained that the Heptapods were originally supposed to give humans “the blueprints to an interstellar ship, like an ark of sorts.” But after Interstellar came out in 2014, they swapped out the ark for language.

“We focused more on what we had there in front of us,” Heisserer said, “which was the power of their language.”

Arrival is a movie about language. It’s about the way we communicate, our failure to listen, our desire to twist language into what we want it to mean, and the consequences of misinterpreting the meaning of words.

At the beginning of the movie, the CIA Idiot wonders why it takes the Heptapods 18 hours to pump fresh air into the room where the humans meet them. He’s suspicious of what they’re doing when they go dark. Ian provides an easy explanation, that the Heptapods need to rebalance the atmosphere for humans. The Heptapods are looking out for them, making sure they don’t die every time they step inside the vessel.

But the CIA Idiot doesn’t see it like that. He misinterprets the logical explanation as a threat, because he’s looking for a reason to choose violence.

“So you’re saying they could suffocate us if they wanted,” he says.

A little later in the movie, after one of their initial meetings with the Heptapods, Colonel G. T. Weber (Forest Whitaker) wants Louise to expedite the process of translating their language. Louise explains why it can’t be rushed.

Weber: Everything you do in there, I have to explain to a room full of men whose first and last question is, “How can this be used against us?” So you’re going to have to give me more than that.

Louise: Kangaroo.

Weber: What is that?

Louise: In 1770, Captain James Cook’s ship ran aground off the coast of Australia, and he led a party into the country, and they met the Aboriginal people. One of the sailors pointed at the animals that hop around and put their babies in their pouch, and he asked what they were, and the Aborigine said, “Kangaroo.”

Weber: And your point is?

Louise: It wasn’t till later that they learned that “kangaroo” means “I don’t understand.” So I need this so that we don’t misinterpret things in there. Otherwise, this is going to take 10 times as long.

Weber: I can sell that for now, but I need you to submit your vocabulary words before the next session.

Louise: Fair.

Weber: And remember what happened to the Aborigines. A more advanced race nearly wiped them out.

[Weber turns and leaves]

Ian: It’s a good story.

Louise: Thanks. It’s not true. But it proves my point.

Much later in the movie, as nations around the globe are on the verge of firing first at the aliens, the Heptapods tell the Russians, “There is no time.” The Heptapods are trying to tell us that there literally is no such thing as time once you learn their language. But the planet misinterprets that line as a threat, that they’re running out of time. It spurs them into action (insert your Russian rushing jokes here). For militarist nations, action equals violence.

Yet at no point do the Heptapods threaten humanity. All they do is communicate with us. All their ships do is hover in our air, above our soil and water and skyscrapers. Their most aggressive act is to hover at a slightly higher elevation than before after an unprovoked attack kills Abbott, which causes absolute (*insert Jonah Hill voice*) mayhem. We interpret their slightest actions as aggression as opposed to self defense. But they’re just trying to help.

It’s a movie about language, so it’s fitting then that the movie doesn’t waste a single word. Its use of language is the movie’s greatest strength. Throwaway lines that don’t seem like they matter do matter once you understand where the movie was heading all along.

The Heptapods’ language gives those who learn it the ability to experience time in a non-linear fashion. In more simpler terms, you’re able to see what we would call the future. Louise is the first to learn their language. It happens at the end of the movie. When she understands it, she’s able to see the rest of her life ahead of her and as a result, she’s able to save the world and the Heptapods, offering a resolution to the chief conflict of the movie, and she makes the decision to fall in love with Ian and have a baby with him even though she now holds the knowledge that their child will die from a rare disease.

It’s a twist that entirely changes the context of the first 100 minutes of the film, but when the twist arrives, you don’t feel cheated. It feels organic. It lands, because you realize the movie hasn’t been leading you astray. It’s you that’s been reading the movie incorrectly. The signs have always been there, we’ve just been interpreting them wrong.

For so much of the movie, we automatically assume the moments with her daughter are flashbacks. Years of watching movies trained us to think this way. We don’t even consider that they could be lookaheads.

When we see Louise’s daughter’s school project, a drawing called “mommy and daddy talk to animals”, we don’t realize that this drawing is something we’ve already seen — Louise and Ian talking to Heptapods — at least not until after the reveal, when everything clicks. When Louise can’t supply the term her daughter is looking for to describe a deal “we both get something out of”, until Ian says it during a meeting with military, CIA, and Louise, at which point Louise tells her daughter the term she’s looking for is “non-zero-sum game”, we think Ian saying the term triggered a flashback for Louise. A few moments later, we realize Louise was able to provide her daughter with the term because she remembered what Ian had said years earlier during that meeting.

It’s a remarkable feat of storytelling, to fit the entire story together like a puzzle without a single piece out of place, but not allowing the audience to see the completed picture until the final piece falls into place.

As Will Leitch wrote for the New Republic at the time, it’s “a movie that plays around with your emotions, but never in a way that feels manipulative.”

“There are twists, but they always feel organic to the story Villeneuve is telling,” Leitch wrote. “He’s playing a trick, but he’s not trying to trick you.”

The evidence the movie presents in support of its eventual conclusion is overwhelming. Louise literally tells us in the film’s opening moments.

“I used to think this was the beginning of your story. Memory is a strange thing, it doesn’t work like I thought it did,” Louise says. “We are so bound by time, by its order.”

When Louise and Ian first meet, Ian reads to her the preface of her book.

“Language is the foundation of civilization,” she wrote. “It is the glue that holds people together. It is the first weapon drawn in a conflict.”

It’s the last line that comes to matter upon repeat viewings of the movie. The Heptapods tell the humans they’re here to offer a “weapon”, which the humans choose to interpret as a threat. But the weapon the Heptapods are trying to give us isn’t something that will harm us. It’s a language.

As Louise wrote, language is the first weapon drawn in a conflict. The film told us in the opening minutes what the Heptapods were offering. The weapon is literally drawn by the Heptapods.

Midway through the movie, Ian mentions that the Heptapods’ “written language has no forward or backward direction. Linguists call this non-linear orthography, which raises the question, ‘Is this how they think?’”

The answer to that question (yes) is the film’s twist. Halfway through the movie, he’s openly asking the question. We just don’t realize the importance of the question.

A little later, Ian and Louise have the following exchange:

Ian: If you immerse yourself into a foreign language, then you can actually rewire your brain.

Louise: Yeah, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. … It's the theory that the language you speak determines how you think and ...

Ian: Yeah, it affects how you see everything.

Again, the movie is telling us that once you learn their non-linear language, you will begin to think non-linearly. But all of the signs (there’s another one involving algebra I decided not to include because I suck at math and I don’t want to try to explain it) don’t click until you realize that the flashbacks that are consuming Louise aren’t actually flashbacks. They’re glimpses into her future. That moment doesn’t occur until Louise herself understands the Heptapods’ language. Then the pieces fall into the place. The moment we, the audience, gain clarity is the exact moment Louise figures out how to use their language and realizes the girl from her visions is her future daughter. Our journey figuring out the puzzle of the movie mirrors her own journey of figuring out their language.

It’s possible the story feels so organic because the process of making it was too.

“I was there for about two weeks, and it was a well-oiled machine,” Heisserer said. “The beauty in that experience was this: Everyone was making the same movie. Seems like such a small statement, but it's nigh impossible to find.”

You don’t need to look beyond the countries in the movie, which shut off communication with each other instead of working together to figure out the Heptapods’ purpose on Earth, to understand what he’s talking about.

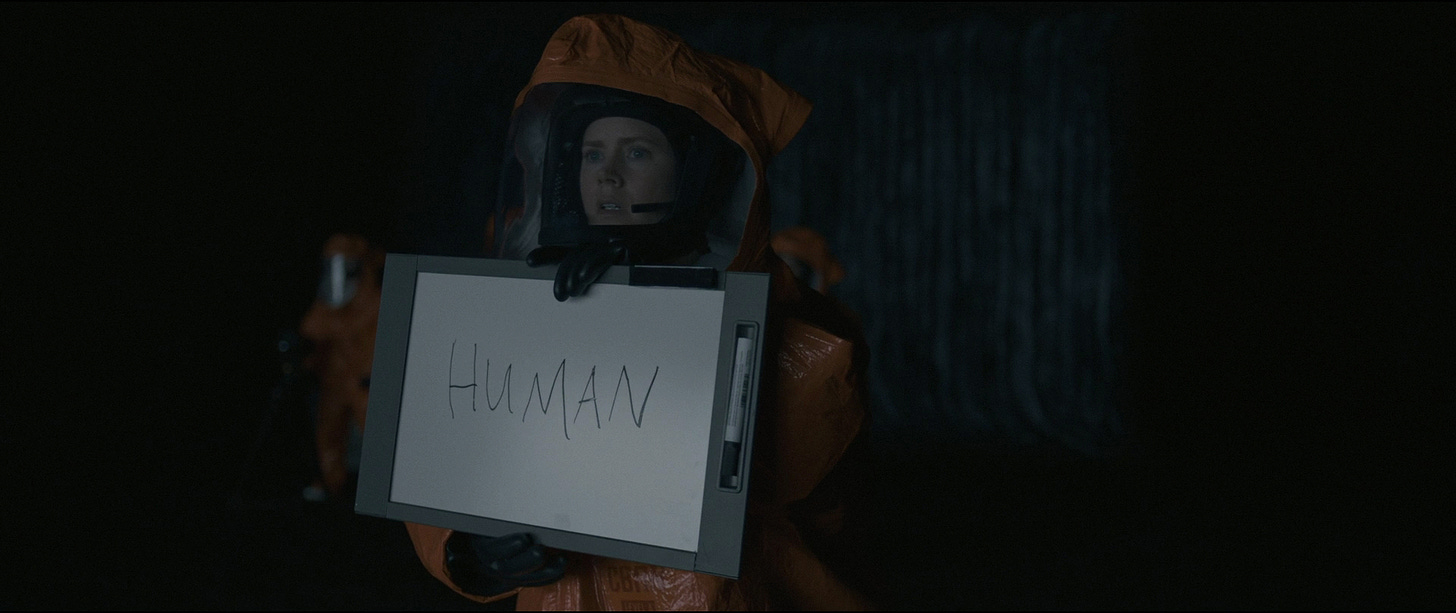

There’s a scene shortly after Louise arrives at the military base where she walks Weber through the question he wants her to ask the Heptapods: “What is your purpose on Earth?” It’s an important scene, meant to demonstrate the complexities of language that we take for granted.

There’s a reason it’s in the movie. Its inclusion came naturally.

“The whiteboard thing came from me defending Louise having to teach basic vocabulary to my producers,” Heisserer said, “where I was showing them why it was so important, and at the end of my diagram of that question they said, ‘THAT is the scene that should go in the movie.’"

Something on the cover of the blu-ray case caught my eye recently. At first, it made me laugh.

“‘Arrival’ is big, grand and marvelous” is such a lame and generic pull quote — no disrespect to Tom Shone, who I assume wrote far better words in his review than the one the movie chose to display.

Arrival’s brilliance isn’t just in its ability to be big. Movies about aliens are supposed to be epic. They’re supposed to be global. And Arrival is both. But it’s also surprisingly deeply personal.

“You know, I’ve had my head tilted up to the stars for as long as I can remember,” Ian tells Louise at the end. “You know what surprised me the most? It wasn’t meeting them. It was meeting you.”

The personal story that Arrival tells somehow matters more than the global aspects of the story.

“All of us wanted to tell this story precisely because it isn't the Hollywood action blockbuster story,” Heisserer said. “It's intimate.”

It’s a story about a mother and a father and their daughter, and a decision without a right answer. As Villeneuve said, “This is a film about mourning.” That too won’t ever age.

When the twist arrives, it allows Louise to save the planet and the Heptapods’ future, but more importantly, it’s the moment she realizes that she’s going to fall in love with Ian, marry him, have a baby they’ll name Hannah (crucially spelled the same backwards and forward), get divorced, and bury their daughter.

“I just realized why my husband left me,” Louise tells Ian at the end of the movie.

“You were married?” he asks with no way of knowing she’s talking about him.

He eventually leaves her because he finds out that she’s known all along that their daughter will die at an early age from a rare disease. Despite knowing this, she decides to proceed anyway. When he, not knowing the fate of their future child at the time, asks her at the end of the movie, “Do you wanna make a baby?”, her smile is unbridled. She says yes twice.

“If you could see your whole life from the start to finish, would you change things?” Louise asks Ian once she realizes where their path together ends.

“Maybe I’d say what I feel more often, I don’t know,” Ian responds, completely oblivious to the intent of the question.

If you side with Ian, you can’t begin to fathom how Louise could welcome a baby in the world knowing that she’ll die at a young age, all without telling him until it’s too late. If you side with Louise, you understand the mix of joy and grief she’s absorbing all at once, and you think the years she allows her daughter to live are worth it.

“So, Hannah, this is where your story begins. The day they departed,” Louise says during the closing montage. “Despite knowing the journey and where it leads, I embrace it. And I welcome every moment of it.”

Arrival is both a powerful warning to the world and a deeply personal movie, which is why it works as well as it does. It’s both epic and intimate, global and personal. Louise saves the world, but that doesn’t feel like the most important moment once you realize what’s going to happen to Louise and Ian.

There’s only one right answer to the overarching story: Louise is correct to save humanity and the Heptapods. But there isn’t one right answer to the decision Louise makes concerning her future marriage and child. It’s a deeply personal decision that varies from person to person. There won’t ever be one right answer.

That won’t ever change, but over time, our answers to the question might.

The duality of the film is reflected beautifully in the cinematography. I won’t pretend to be an expert in cinematography. I can barely take a clear photo using my iPhone. But the imagery in Arrival is undeniable. Just like how there isn’t a wasted line of dialogue, there also isn’t a wasted shot.

The cinematography reflects both the epic and intimate sides of the story. So often, we’re presented with big vs. small.

Whether it’s Louise touching the glass with her normal-sized hand only to be met by the Heptapods’ version of a hand.

Or the sight of the Heptapods, which tower over Louise …

…. through the lens of a camera:

Villaneuve and cinematographer Bradford Young so effectively disorient us for the same journey that Louise is experiencing. Everything related to the Heptapods is shrouded in fog.

From the alien vessel.

To their side of the room on the other side of the looking glass.

But when Louise is shown in her house, monologuing about Hannah before and after we realize what she’s decided to do, looking through the wide panes of glass that so clearly mirror the looking glass in the alien ship, the view ahead is clear.

At the beginning.

And again at the end.

She embraces her decision. She welcomes the journey. She sees it clearly.

It’s also about color. The color palette used in the lookaheads stand in stark contrast to the color palette used in the present.

The present is dreadfully grey.

The lookaheads to Hannah are alive with color.

When the lookaheads begin — after Louise achieves a breakthrough with the Heptapods’ written language — she doesn’t understand who the girl is and why she’s experiencing them. Later, Costello tells her, “Louise has weapon. Use weapon.”

The cinematography repeatedly tells us this too.

There it is, their language, already in her head. She just doesn’t know it yet.

If you watched this year’s Academy Awards, you know that music plays a big role in movies — thank you to the Academy for teaching us this important lesson we did not already know. The problem with writing about music is that it’s not easy to describe music without sounding pretentious.

I’ll just say this: For the opening and closing montages that Louise monologues over, Villeneuve’s choice is beyond reproach. Even though the movie’s score is composed by the late Johan Johansson, the film’s pivotal opening and closing moments belong to Max Richter’s On The Nature Of Daylight.

The decision to borrow a song from Richter proved to be costly from an Academy Awards perspective — it was disqualified from Best Score — but the decision also cemented Arrival’s ending as one of the best endings I’ve ever seen. Do yourself a favor and listen to a few minutes of On The Nature Of Daylight. It’s distressingly beautiful and conveys the emotions that Louise is experiencing upon realizing the decision she’s making.

Richter is also heralded for his work on HBO’s The Leftovers. Ironically enough, the iconic song from The Leftovers’ score is titled The Departure.

“We are so bound by time,” Louise says in the monologue that begins the film, “by its order.”

She’s not talking about movies of course, but she could be. Movies are inherently constrained. They have a beginning, middle, and end. They have a run-time. They have a budget. Most have a shelf-life. At a certain point, they become dated.

Arrival isn’t unlike other movies in that regard. Sure, it has a run-time (116 minutes). It had a budget ($47 million). At some point, the special effects will become dated, though that day hasn’t arrived yet.

But it isn’t bound by time. As long as humanity, Earth, and language exists, Arrival will have staying power. It’ll have resonance.

Even though I know how it ends, even though I can identify every line of dialogue and every shot that foreshadows the ending, even though the ending never fails to wreck me, I’ll keep rewatching it.

Despite knowing the journey and where it leads, I embrace it. And I welcome every moment of it.

God. This was wonderful.

Incredible job Sean! Arrival really is a story of grief and pain. I’ll never forget how sad I felt for Abbott. Ultimately choosing to come help Earth yet knowing you’d meet your fate in doing so. Powerful stuff.